Installeer de app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Opmerking: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Je gebruikt een verouderde webbrowser. Het kan mogelijk deze of andere websites niet correct weergeven.

Het is raadzaam om je webbrowser te upgraden of een browser zoals Microsoft Edge of Google Chrome te gebruiken.

Het is raadzaam om je webbrowser te upgraden of een browser zoals Microsoft Edge of Google Chrome te gebruiken.

Privacy (op computer, telefoon en meer)

- Onderwerp starter Medusa

- Startdatum

Lievergezond

Well-known member

Lievergezond

Well-known member

Lievergezond

Well-known member

LinkedIn gaat gebruikersdata gebruiken voor AI-modellen, maar je kunt afmelden

LinkedIn gaat de data van Nederlandse en andere Europese gebruikers binnenkort inzetten om AI-modellen te trainen. Wie dat niet wil, moet zichzelf afmelden. Het trainen gebeurt op basis van openbare posts, maar niet op privéberichten.

Lievergezond

Well-known member

In winkels vraagt men vaak naar het bezit van klantenkaarten.

Laatste keer kocht ik ergens een paar schoenen.

En dan de achteloosheid: ''mag ik uw postcode''.

Ik liet expres een extra lange stilte vallen.

Dat hielp gelukkig gelijk zodat die kassiere niet op die toer verder ging.

Vandaag dus weer of ik een klantenkaart heb (bij Holland & Barrett).

Ik heb ooit een keer bij een ''nee'' een enorme sneer gekregen bij het horlogebandje verwisselen in de ''Lucardi'': die wilde ook ff al mijn gegevens.

Praat ik wel over 15 jaar terug.

Vandaag heb ik gewoon keihard teruggeschoten meteen zonder met 'nee' terug te komen.

Ik zei vrij beslist zodat ook klanten achter mij het konden horen: ''ik hecht aan mijn privacy''.

Ze wilde me ervoor een een klantenkaart aansmeren namelijk of dat ik een emailadres had voor haar.

Gelukkig kun je dat privacy-argument steeds makkelijker noemen tegenwoordig zonder raar aangekeken te worden.

Laatste keer kocht ik ergens een paar schoenen.

En dan de achteloosheid: ''mag ik uw postcode''.

Ik liet expres een extra lange stilte vallen.

Dat hielp gelukkig gelijk zodat die kassiere niet op die toer verder ging.

Vandaag dus weer of ik een klantenkaart heb (bij Holland & Barrett).

Ik heb ooit een keer bij een ''nee'' een enorme sneer gekregen bij het horlogebandje verwisselen in de ''Lucardi'': die wilde ook ff al mijn gegevens.

Praat ik wel over 15 jaar terug.

Vandaag heb ik gewoon keihard teruggeschoten meteen zonder met 'nee' terug te komen.

Ik zei vrij beslist zodat ook klanten achter mij het konden horen: ''ik hecht aan mijn privacy''.

Ze wilde me ervoor een een klantenkaart aansmeren namelijk of dat ik een emailadres had voor haar.

Gelukkig kun je dat privacy-argument steeds makkelijker noemen tegenwoordig zonder raar aangekeken te worden.

gse

Well-known member

Gewoon slimmer mee omgaan. Soms geeft dit wel korting op je nodige inkopen. Gebruik gewoon een andere mailadres (of alias) voor bedrijven. Ik ga zelfs zover dat ik vele bedrijven hun "eigen" mailadres geef. Dan weet bijvoorbeeld (meer dan 10 jaar geleden). Dat de Rabobank gehackt was. Ik kreeg een mail met de bekende vragen voor inkomen, adres, etc. afkomstig van rabobank@voorbeeldurl.nl. De Rabobank heeft nooit terug gereageerd toen ik het melde. Nog een leuk voorbeeld, zo claimde een Unive medewerker dat ik de naam niet in een mailadres mocht gebruiken....In winkels vraagt men vaak naar het bezit van klantenkaarten.

Laatste keer kocht ik ergens een paar schoenen.

En dan de achteloosheid: ''mag ik uw postcode''.

Ik liet expres een extra lange stilte vallen.

Dat hielp gelukkig gelijk zodat die kassiere niet op die toer verder ging.

Vandaag dus weer of ik een klantenkaart heb (bij Holland & Barrett).

Ik heb ooit een keer bij een ''nee'' een enorme sneer gekregen bij het horlogebandje verwisselen in de ''Lucardi'': die wilde ook ff al mijn gegevens.

Praat ik wel over 15 jaar terug.

Vandaag heb ik gewoon keihard teruggeschoten meteen zonder met 'nee' terug te komen.

Ik zei vrij beslist zodat ook klanten achter mij het konden horen: ''ik hecht aan mijn privacy''.

Ze wilde me ervoor een een klantenkaart aansmeren namelijk of dat ik een emailadres had voor haar.

Gelukkig kun je dat privacy-argument steeds makkelijker noemen tegenwoordig zonder raar aangekeken te worden.

Wordt er gespamd op een mailadres, dan sluit je het gewoon of je laat het automatisch naar de prullenbak gaan.

Uiteraard koppel ik nooit een telefoonnummer, geboortedatum of adres aan deze mail adressen.

Uiteraard weten de grote Online bedrijven (Facebook, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, etc) via IP adres en computer "fingerprints" wel wie je bent. Als je echt privacy will, heb je nooit een contact met deze bedrijven en kun je redelijk privé online gaan. En anders dan ook maar niet online gaan.

Lievergezond

Well-known member

Wel een goed punt gse.

Aan de andere kant gaat het me er ook om dat die ander geconfronteerd wordt met dat die me lastig valt.

In de winkel zou ik ook gewoon een fake postcode kunnen opgeven bijv. : iedereen blij of zo.

Maar goed, nogmaals: het gaat me erom ook in het contact dat ze begrijpen dat ik meer ben dan een datamelkkoe en dat ze uit hun flow gehaald worden.

Ik heb me wel eens over laten halen zo'n kaart te nemen en dan kreeg ik korting maar dan heb ik me nooit aangemeld.

En dan daarna ging die winkeldame zo keihard roepen dat ik me NOG STEEDS NIET HAD AANGEMELD.

Ja boeien natuurlijk.

Maar je wordt gewoon gestalked en lastig gevallen of je nou wil of niet: of je het spelletje meespeelt of niet.

Ik heb het op mijn werk ook (gehad): dat collega's me voor bepaalde workshops verplicht stelden.

En dan wilden ze nog een ''ja'' van mij en dat kregen ze dan niet.

En dat ging dan tot en met dat ze mijn leidinggevende gingen zeggen dat ik niet meedeed ''terwijl er niks anders mijn agenda stond''(geen andere verplichtingen).

Het ging ook nog om een totaal NUTTELOZE workshop die erover ging dat we nu dan weer zelf het werk moesten gaan doen dat zij eerst naar zich toe hadden getrokken waarvan we in een vorige workshop hadden geleerd dat zij dat werk zouden moeten gaan doen (communicatie: totaal nutteloze bezigheid).

En dan had je ook van die slimmerikken die dan gewoon voor de vorm iets anders te doen hadden en die kregen die confrontatie dan niet die ik wel kreeg met mijn eigen baas die tegen me stond te schreuwen ook nog.

En dan zei hij: begrijp je me?

Dan zei ik: ja hoor, ik begrijp je, maar ik accepteer het niet hahahahahaha.

Aan de andere kant gaat het me er ook om dat die ander geconfronteerd wordt met dat die me lastig valt.

In de winkel zou ik ook gewoon een fake postcode kunnen opgeven bijv. : iedereen blij of zo.

Maar goed, nogmaals: het gaat me erom ook in het contact dat ze begrijpen dat ik meer ben dan een datamelkkoe en dat ze uit hun flow gehaald worden.

Ik heb me wel eens over laten halen zo'n kaart te nemen en dan kreeg ik korting maar dan heb ik me nooit aangemeld.

En dan daarna ging die winkeldame zo keihard roepen dat ik me NOG STEEDS NIET HAD AANGEMELD.

Ja boeien natuurlijk.

Maar je wordt gewoon gestalked en lastig gevallen of je nou wil of niet: of je het spelletje meespeelt of niet.

Ik heb het op mijn werk ook (gehad): dat collega's me voor bepaalde workshops verplicht stelden.

En dan wilden ze nog een ''ja'' van mij en dat kregen ze dan niet.

En dat ging dan tot en met dat ze mijn leidinggevende gingen zeggen dat ik niet meedeed ''terwijl er niks anders mijn agenda stond''(geen andere verplichtingen).

Het ging ook nog om een totaal NUTTELOZE workshop die erover ging dat we nu dan weer zelf het werk moesten gaan doen dat zij eerst naar zich toe hadden getrokken waarvan we in een vorige workshop hadden geleerd dat zij dat werk zouden moeten gaan doen (communicatie: totaal nutteloze bezigheid).

En dan had je ook van die slimmerikken die dan gewoon voor de vorm iets anders te doen hadden en die kregen die confrontatie dan niet die ik wel kreeg met mijn eigen baas die tegen me stond te schreuwen ook nog.

En dan zei hij: begrijp je me?

Dan zei ik: ja hoor, ik begrijp je, maar ik accepteer het niet hahahahahaha.

Laatst bewerkt:

Mike

Medusa

Well-known member

Voor wie met windows 10 wil blijven werken:

www.schoonepc.nl

www.schoonepc.nl

Q&A: Kan ik mijn Windows 10 pc na 14 oktober 2025 nog gebruiken?

Q&A: Kan ik mijn Windows 10 pc na 14 oktober 2025 nog gebruiken?

Lievergezond

Well-known member

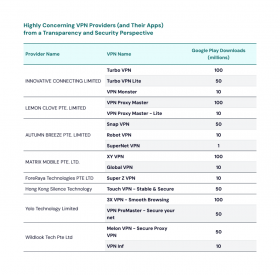

Who Owns, Operates, and Develops Your VPN Matters: An analysis of transparency vs. anonymity in the VPN ecosystem, and implications for users

New research: Eight popular, commercial VPN apps operate deceptively and put more than 700 million users at risk of authoritarian surveillance.

www.opentech.fund

Who Owns, Operates, and Develops Your VPN Matters: An analysis of transparency vs. anonymity in the VPN ecosystem, and implications for users

New research: Eight popular, commercial VPN apps operate deceptively and put more than 700 million users at risk of authoritarian surveillance.

Tue, 2025-09-02 13:40

New research from ICFP Fellow Benjamin Mixon-Baca finds that eight providers of popular, commercial VPN applications appear to hide the ownership and operations of their services, and contain serious privacy and security issues that put more than 700 million users at risk of authoritarian surveillance. Three of these providers are linked to the PLA and there is evidence that a Chinese national owns all eight.

Key Findings:

- Commercial VPNs serving over 700 million users with poor transparency standards permit attackers to remove encryption, a glaring security and privacy vulnerability.

- A first group of VPNs has established links to China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and a second group—with similarly deceptive practices—was newly discovered.

Why VPN Transparency Matters

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) are critical security and privacy infrastructure used by people globally to circumvent repressive censorship and surveillance, and protect their privacy and connections on public WiFi. They have grown significantly in popularity as more authoritarian governments censor the free and open internet.

Commercial VPN providers operate with varying degrees of transparency and users must determine whether they value transparency more than anonymity when choosing a provider, as there are trade-offs with each.

Transparency vs. Anonymity in the VPN Ecosystem

VPNs are not designed for truly anonymous communications. When selecting a VPN provider, users are implicitly transferring trust from their internet service provider to the VPN provider. This transfer—despite often being overlooked or ignored—carries with it significant security implications, given the access the provider has to the user’s data.

The benefit of a transparently operating VPN provider is that users know who can view their communications. The limitation of such a provider is that it can be identified easily by authorities and subpoenaed or targeted by cyber criminals, which could put users at risk.

A VPN provider that operates anonymously (so less transparently) cannot be easily targeted by censors or cyber criminals, or subpoenaed by authorities—providing a level of protection to users. The downside is users do not know who can view their communications, which could increase their risk of surveillance or exploitation.

Information about a provider’s operations, ownership, and development is key for users to make informed decisions, but these details are often hard to find. In addition, some VPN providers—particularly the free services that monetize user data and serve ads—use ethically questionable practices when developing, marketing, and operating their VPNs. They take advantage of legal loopholes and attempt to hide who controls their services. For example, there are VPNs who cite Singapore (a country with strong privacy laws) as their country of origin on app stories—yet they are actually linked to China (a country with highly invasive privacy laws).

When VPN provider information such as this is not easy to find or the provider actively tries to hide this information, users risk entrusting their data to a provider that they might not have chosen otherwise. In contexts where individuals are prosecuted for expressing themselves online or accessing information that authorities blacklist, these types of VPNs put their users at great risk.

Project Overview

In an effort to bring greater visibility into the VPN ecosystem, Information Controls Fellowship Program (ICFP) fellow Benjamin Mixon-Baca, collaborated with Dr. Jeffrey Knockel of Bowdoin College and Dr. Jedidiah R. Crandell of Arizona State University to uncover who owns, operates, and develops 32 popular VPNs on the Google Play Store (with more than one billion downloads, collectively). These VPN apps are distributed by 21 seemingly distinct VPN providers and serve users in India, Indonesia, Russia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, UAE, Bangladesh, Egypt, Algeria, Singapore, and Brazil.

They assigned the providers a multi-factor “transparency versus anonymity” score, with the goals of:

Mixon-Baca and his fellow researchers also examined if there is a link between less transparency and security vulnerabilities.

- helping users make more informed decisions when selecting a VPN provider; and

- encouraging app stores to clearly identify apps that operate transparently and those that do not.

Significant Findings

1. Two clusters of VPN providers—whose apps have more than 700 million downloads, collectively—have egregious transparency offenses.

Two groups of providers do not disclose that they are related or operate together, and appear to hide the ownership and operations of their services.

Previous research found that the first cluster—INNOVATING CONNECTING LIMITED, AUTUMN BREEZE PTE. LIMITED, and LEMON CLOVE PTE. LIMITED— are operated by the same Chinese national [1] and have links to the Chinese cybersecurity firm Qihoo 360 and the PLA [2] by examining their privacy policies and copyright filings. Mixon-Baca’s research dug deeper by manually analyzing their most popular VPN apps, and found that they also share code and infrastructure—even stronger indications of connection.

The second cluster of concerning VPN providers, which previous research has not investigated, includes MATRIX MOBILE PTE. LTD., ForeRaya Technologies PTE LTD, Wildlook Tech Pte Ltd., Hong Kong Silence Technology, and Yolo Technology Limited. While connections to Qihoo 360 could not be identified for these entities, their operational characteristics are similar to the first cluster (which does have ties to the Chinese cybersecurity firm). For example, their privacy policies reference Innovative Connecting. In addition, their apps share infrastructure and code.

2. Both clusters have a number of security vulnerabilities.

The vulnerabilities include:

These software issues are alarming, especially for the providers with links to the Chinese cybersecurity firm Qihoo 360. It calls into question the providers’ intentions when they are connected to the biggest cybersecurity firm in China, yet offer security-critical applications with glaring vulnerabilities.

- The use of Shadowsocks for tunneling: Shadowsocks (an open source proxy project designed to bypass internet censorship and geo-restrictions) was designed for access to the open internet only, and not for confidentiality—this is problematic as these apps are advertised as providing user security.

- Hard-coded passwords in their configuration that are shared across all users: The password is embedded within the source code, instead of stored securely elsewhere and retrieved at runtime. The fact that the password credentials are in the app code itself, makes them easily accessible to anyone who can view the code. An attacker who knows the password can decrypt the VPN’s encryption for all users, exposing the content they are accessing. This significantly compromises user security and privacy.

- Susceptibility to blind-in/on-path client/server-side attacks (client side confirmed, server side implied): An attacker can intercept and even modify communication without the knowledge of the user, a serious violation of their privacy and security.

- Extraction of user location information, despite claiming that this is not collected.

3. Free commercial VPN apps are riskier than paid ones.

While not all free commercial VPN apps operate in poor faith, using products such as TurboVPN, VPN Proxy Master and Snap VPN (supplied by the first cluster of providers), presents far more risk to user security and privacy than using a paid VPN app. This is because free commercial VPNs tend to capitalize on their users’ data, potentially using ethically questionable practices in their development, marketing, and operations.

Laatst bewerkt:

Medusa

Well-known member

De procureur-generaal van Texas, Ken Paxton, heeft zojuist een schikking van 1,375 miljard dollar tegen GOOGLE gewonnen. Dat is de grootste schikking ooit, met één staat.

Wat Google deed zou iedereen moeten shockeren…

- Onrechtmatige locatiebepaling: Zelfs nadat gebruikers de locatiegeschiedenisfuncties op hun Android- of iOS-apparaten hadden uitgeschakeld, bleef Google geolocatiegegevens verzamelen en opslaan ZONDER TOESTEMMING.

- De 'incognito'- of privébrowsefunctie van Google in Chrome werd gepromoot als een functie die geen zoekgeschiedenis of locatieactiviteit bijhoudt. Google verzamelde en gebruikte deze gegevens NOG STEEDS voor reclame en andere doeleinden.

- Ongeautoriseerde verzameling van biometrische gegevens: Google heeft gevoelige biometrische identificatiegegevens vastgelegd en OPGESLAGEN, zoals stemopnames (van gesproken zoekopdrachten of interacties met de Assistent) en gezichtsgeometrie (van fotoanalyse in services zoals Google Foto's) - ZONDER geïnformeerde toestemming te verkrijgen.

Zoals ik altijd al zei: data is waardevoller dan goud.

Bedankt @KenPaxtonTX

!

Mag Google de biometrische gegevens die zij ILLEGAAL hebben verzameld nog steeds bewaren?

Wat Google deed zou iedereen moeten shockeren…

- Onrechtmatige locatiebepaling: Zelfs nadat gebruikers de locatiegeschiedenisfuncties op hun Android- of iOS-apparaten hadden uitgeschakeld, bleef Google geolocatiegegevens verzamelen en opslaan ZONDER TOESTEMMING.

- De 'incognito'- of privébrowsefunctie van Google in Chrome werd gepromoot als een functie die geen zoekgeschiedenis of locatieactiviteit bijhoudt. Google verzamelde en gebruikte deze gegevens NOG STEEDS voor reclame en andere doeleinden.

- Ongeautoriseerde verzameling van biometrische gegevens: Google heeft gevoelige biometrische identificatiegegevens vastgelegd en OPGESLAGEN, zoals stemopnames (van gesproken zoekopdrachten of interacties met de Assistent) en gezichtsgeometrie (van fotoanalyse in services zoals Google Foto's) - ZONDER geïnformeerde toestemming te verkrijgen.

Zoals ik altijd al zei: data is waardevoller dan goud.

Bedankt @KenPaxtonTX

!

Mag Google de biometrische gegevens die zij ILLEGAAL hebben verzameld nog steeds bewaren?

Lievergezond

Well-known member

Lievergezond

Well-known member

''Recent maakte de Belastingdienst bekend zijn digitale kantooromgeving bij techbedrijf Microsoft onder te brengen. Dat gebeurt ondanks kritiek van deskundigen, die zeggen dat de Amerikanen op die manier wel heel makkelijk bij onze privégegevens kunnen komen.''

www.nu.nl

www.nu.nl

Overheid verliest grip op ICT: 'Moeten stoppen met deze waanzin'

Door Rutger Otto

28 okt 2025 om 05:03Update: 1 week geleden

1K reacties

Delen

Het gaat in aanloop naar de verkiezingen opvallend weinig over digitalisering. Dat terwijl het IT-beleid van de overheid al jaren onder druk staat. Deskundigen waarschuwen dat er hoognodig iets moet veranderen.

De Nederlandse overheid heeft de grip op haar ICT de afgelopen jaren verloren. Er zijn daarvoor tal van voorbeelden te noemen. Recent maakte de Belastingdienst bekend zijn digitale kantooromgeving bij techbedrijf Microsoft onder te brengen. Dat gebeurt ondanks kritiek van deskundigen, die zeggen dat de Amerikanen op die manier wel heel makkelijk bij onze privégegevens kunnen komen.

Ook op andere plekken gaat het mis. Begin dit jaar kampte het Openbaar Ministerie met een flinke storing vanwege "verouderde ICT-infrastructuur". Daardoor konden dertienhonderd medewerkers niet inloggen en gingen rechtszaken niet door.

Daarnaast is er aanhoudend gedoe met het communicatiesysteem C2000 voor hulpdiensten, rijzen de kosten van ICT bij de gemeenten de pan uit en blijkt de overheid niet goed voorbereid op langdurige uitval van computersystemen.

Al het gedoe met digitalisering en ICT lijkt soms abstract, maar toch heeft iedereen ermee te maken. Als de belastingaangifte niet werkt door een storing, als DigiD platligt of als je geen paspoort kunt aanvragen, treft dat elke burger.

Pleisters plakken op systemen die niet goed meer werken

ICT-systemen zijn door de jaren heen zeer complex geworden, omdat er weinig structurele verbeteringen zijn gekomen die de problemen bij de wortels aanpakken. "De aandacht ligt vaak bij het oplossen van incidenten", zegt Mariette Lokin, bijzonder hoogleraar Wetgeven in de digitale rechtsstaat aan de Open Universiteit. "Maar dat komt neer op pleisters plakken op overheidssystemen, waardoor de complexiteit toeneemt."

Ook Onno Eric Blom ziet het misgaan. Hij is directeur van stichting Herprogrammeer de overheid. "Nederland koopt grote systemen in die dertig jaar meegaan", zegt hij. "Daarna vallen ze uit elkaar en kunnen we geen regelgeving meer doorvoeren."

In de techindustrie is een computersysteem geen eenmalige aanschaf, zegt Blom. "We moeten stoppen met de waanzin dat we systemen van 200 miljoen euro inkopen met het idee dat we daarna klaar zijn."

Blom zegt dat de overheid ICT moet zien als een levend product dat constant aandacht nodig heeft. Ze moeten onderhouden en verbeterd worden, zoals dat ook gebeurt met apps en websites. Ook ziet hij heil in het opzetten van een digitale dienst die de overheid helpt en al tijdens de beleidsontwikkeling prototypes van ICT-systemen bouwt. "Zo kom je erachter wat haalbaar is en voorkom je 80 procent van de problemen."

ICT bij de overheid is versnipperd

In het huidige ICT-landschap ontbreekt die centrale regie. Gemeenten kiezen hun eigen software, ministeries werken met eigen programma's en er is geen centrale organisatie. Er worden voor overheidssystemen vaak aanbestedingen bij externe bedrijven gedaan die veel geld kosten en vaak vertraging oplopen.

De Rijksoverheid wil dat daar verandering in komt, blijkt uit de eerder dit jaar gepresenteerde Nederlandse Digitaliseringsstrategie. De strategie pleit onder meer voor een betere samenwerking van overheidsorganisaties en minder afhankelijkheid van buitenlandse techbedrijven. "Digitalisering staat nu ook politiek hoog op de agenda", staat op de website.

Daar twijfelen de deskundigen aan, zeker na de val van het kabinet. "Door het demissionaire kabinet blijven veel zaken liggen", zegt Lokin. "En doordat kabinetten elkaar snel opvolgen, worden strategieën niet uitgevoerd, waardoor weinig vooruitgang wordt geboekt."

Technische kennis ontbreekt

"De Nederlandse overheid beschouwt digitalisering als iets wat anderen maar moeten doen", zegt Bert Hubert, IT-expert en voormalig toezichthouder op de AIVD en MIVD. "De minister heeft geen kennis en de beleidsstaf weet er niet veel van. Als je een willekeurig persoon op straat om IT-advies vraagt, krijg je een nuttiger antwoord dan van iemand bij ons aan de top."

Hubert, Blom en Lokin zien graag dat er meer technische kennis op topfuncties bij de overheid komt. "Bij managerfuncties wordt nu vooral verwacht dat je goed bent in leidinggeven", zegt Blom. Hij noemt het belangrijk dat beleidsmakers in een digitale samenleving ook verstand hebben van technologie.

In werkelijkheid wordt vaak voor efficiëntie gekozen. Als de problemen met ICT zich opstapelen, lijkt het misschien handiger om de oplossingen uit te besteden. Blom heeft in principe niets tegen hulp van buitenaf, al waarschuwt hij wel dat daar goed over moet worden nagedacht: "Gooi de regie van onze digitale overheid niet over de schutting."

Hubert vult aan dat computersystemen in deze tijd het hart van het land vormen. "Er zijn soms storingen, maar over het algemeen werkt de dienstverlening wel. Het is alleen zo dat we de Amerikanen alles laten regelen, waardoor zij ook toegang krijgen tot gevoelige gegevens. Wat als we ooit ruzie krijgen met de VS of de rekening wordt te duur? Hebben we dan een back-up?"

Geen onderwerp tijdens verkiezingen

Voorafgaand aan de Tweede Kamerverkiezingen van woensdag speelt digitalisering nauwelijks een rol. Op de kieslijsten staan kandidaten met een digitaal profiel op vrijwel onverkiesbare plekken.

De aanstelling van een minister voor Digitale Zaken lijkt daarmee steeds lastiger te worden, terwijl het Adviescollege ICT-toetsing daar al jaren voor pleit. Het Adviescollege noemt zo'n minister belangrijk voor een betrouwbare digitale overheid.

Lokin hoopt dat partijen tijdens de formatie alsnog tot concrete plannen komen voor het verbeteren van de Nederlandse digitalisering. Ze hoopt ook dat de komende regering aan uitvoeringsorganisaties de ruimte biedt om dat voor elkaar te krijgen.

"Soms wordt gezegd: doe het gewoon. Maar dat is niet zo simpel als het lijkt", zegt Lokin. "Er moet expliciet prioriteit en aandacht komen om het verbeteren van overheids-ICT grootschalig aan te pakken. Bij de uitvoeringsorganisaties zit veel innovatiekracht die nu niet wordt benut."

Overheid verliest grip op ICT: 'Moeten stoppen met deze waanzin'

Het gaat in aanloop naar de verkiezingen opvallend weinig over digitalisering. Dat terwijl het IT-beleid van de overheid al jaren onder druk staat. Deskundigen waarschuwen dat er hoognodig iets moet veranderen.

Lievergezond

Well-known member

Dat zeggen ze ook van de stemmachines/software: iets met Servie in samenwerking met ik geloof Venezuela o.i.d.Ach ja, gewoon 'outsourcing'.

Postcodeloterijtrekking is bijv. al sinds jaren ondergebracht bij de Italiaanse maffia.

Just business (nothing personal)

Laatst bewerkt:

En als je dan die opties uitzet worden al je fb-bijdragen vervolgens gewoon nog met wat extra aandacht gevolgd

Lievergezond

Well-known member

Mijn gedachteEn als je dan die opties uitzet worden al je fb-bijdragen vervolgens gewoon nog met wat extra aandacht gevolgd

Medusa

Well-known member

De EU : “We hebben geluisterd naar de zorgen over privacy, dus Chatcontrol is tijdelijk van de baan”

Vijf minuten later: “Dus we werken aan iets nieuws om jullie beter te beschermen.

Tegen… alles eigenlijk.”

Het resultaat?

Een Europese KGB: geen spionnen in burger, geen veldoperaties, alleen ambtenaren die nationale inlichtingen parkeren in Brussel en elkaar vriendelijk verzekeren dat dit voor onze eigen veiligheid is.

www.hln.be

www.hln.be

Vijf minuten later: “Dus we werken aan iets nieuws om jullie beter te beschermen.

Tegen… alles eigenlijk.”

Het resultaat?

Een Europese KGB: geen spionnen in burger, geen veldoperaties, alleen ambtenaren die nationale inlichtingen parkeren in Brussel en elkaar vriendelijk verzekeren dat dit voor onze eigen veiligheid is.

“Europese Unie bezig met oprichting nieuwe inlichtingendienst”

De Europese Commissie is bezig met de oprichting van een nieuwe inlichtingendienst. Dat meldt de krant ‘Financial Times’. De nieuwe eenheid moet het gebruik verbeteren van informatie die is verzameld door nationale veiligheidsdiensten.

Forum statistieken